서 언

재료 및 방법

실험재료

추출물 제조

환원력과 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성 측정

세포배양

Nitric oxide (NO)와 cytokine (PGE2, TNF-𝛼 및 IL-1𝛽) 측정

단백질 추출 및 Western blot analysis

통계 처리

결과 및 고찰

EMS의 항산화 활성

EMS가 RAW264.7 세포 생존에 미치는 영향

EMS가 iNOS, COX-2 발현 및 NO, PGE2의 생성에 미치는 영향

EMS가 pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-𝛼, IL-1𝛽)의 발현 및 생성에 미치는 영향

EMS가 TLR4/NF-𝜅B 신호전달 경로에 미치는 영향

적 요

서 언

Haloragaceae (개미탑)과에 속하는 이삭물수세미(Myriophyllum spicatum L.)는 저수지, 하천 등에서 자라는 여러해살이풀로 침수성 수생식물이고, 유럽, 아시아, 남아프리카, 북반구 한대, 냉대 및 온대 지역에 분포하며 우리나라에서는 경기도, 강원도, 경상남도, 전라도 등에 난다(Cui et al., 2008). 식물체는 자웅동주이고, 줄기는 0.8-2 m로 길게 신장되며, 잎은 거의 물속에 잠겨 자라난다. 물 밖으로 돌출되는 잎은 대개 급격하게 축소되어 포의 형태로 된다. Nakai et al. (2005)에 의하면 이삭물수세미는 타감 작용이 있고, anti-cyanobacterial 작용으로 남세균의 성장을 억제하여 녹조현상을 막는 효과가 있다고 보고되었고, 주요 성분으로는 eugeniin, 4개의 polyphenol (ellagic acid, gallic acid, pyrogallic acid 및 (+)-catechin 등) 및 다양한 지방산이 분리되었다고 보고된 바 있다(Gross et al., 1996; Nakai et al., 2000). 또한, 연못이나 수조에 관상용으로도 사용되지만, 민간에서는 전초를 고름, 염증 등에 약용으로 사용하였다. 이삭물수세미의 남세균 억제효과에 대한 연구는 존재하나(Nakai et al., 2005), 염증에 대한 연구가 미비하기에 이삭물수세미의 항염증 효과에 대한 연구를 수행하였다.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)은 일반적으로 정상적인 대사 과정에서 생성되며 세포 신호 및 항상성에 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Chainy and Sahoo, 2020). 자외선, 환경적 스트레스, 질병 등과 같은 산화적 스트레스에 의해 증가된 활성산소는 세포를 손상시키고 신체에 해로우며, 만성피로, 고지혈증, 동맥경화, 심장질환, 말초혈관질환, 알레르기성 피부염, 암, 노화 및 신장질환을 유발하고 기존 질환을 악화시킨다고 알려져 있다(Meléndez‐Martínez, 2019).

ROS 과잉 생산을 방지하기 위해 국소 염증이 유도되는데(Chelombitko, 2018), 이러한 이유는 염증이 여러 자극(유해한 자극, 물리적 자극, 화학적 자극)에 의해 활성화되는 필수적인 방어기작이기 때문이다(Kim et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2021b). 과도하게 발현된 염증인자들은 관절염, 다발성 경화증 또는 암과 같은 질병과 관련된 만성 질환 상태로 발전하기도 한다(Atreya and Neurath, 2005; Guzik et al., 2003). 또한 과도한 염증반응은 각종 질병을 악화시키게 된다(Kim and Kang, 2019). 대부분의 과도한 염증반응은 pro-inflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor(TNF)-α와 interleukin(IL)-6]과 pro-inflammatory mediator [nitric oxide (NO)와 prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)]를 생성하는 염증성 세포를 활성화시킨다(Kim et al., 2017). iNOS와 COX-2 단백질의 발현은 각각 NO와 PGE2를 합성하여 생성시킨다(Kim et al., 2021a). 염증반응에 있어서 pro-inflammatory mediator로 잘 알려진 NO와 PGE2는 염증반응 정도를 판단하는 척도로 이용되고 있고(Lee et al., 2019), pro-inflammatory cytokines으로 알려진 TNF-α와 IL-1β와 같은 유전자들을 발현시킴으로써 염증반응이 일어난다(Church and McDermott, 2009; Lee, 2011). 염증을 유도하는 대표적인 물질로는 그람음성세균으로부터 유래된 내독소(endotoxin)인 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)가 알려져 있다(Lee et al., 2019). LPS는 세포 내 다양한 신호전달 경로를 활성화시켜 염증을 발현시킨다(Cheng et al., 2014). 이러한 신호전달 경로 중 toll-like receptor (TLR) family에 속한 TLR4는 병원체(LPS)에 대한 면역 반응의 주요 매개체 역할로 pro-inflammatory 반응을 활성화 시킨다(Jeong et al., 2014). LPS에 의한 TLR4의 활성화는 myeloid differentiation protein (MyD)88과 같은 신호전달 인자를 통해 nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) 등과 같은 하위 신호 전달 경로의 활성화를 유발하여 궁극적으로 염증 관련 유전자의 발현을 유도한다고 알려져 있다(Anwar et al., 2013). 따라서, TLR4에 대한 길항제는 차등 표적 유전자 발현 및 세포 반응을 억제함으로써 pro-inflammatory cytokines (iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β) 등과 같은 pro-inflammatory 신호 전달 경로를 비활성화할 수 있다(Seo and Jeong, 2020). 염증성 질환은 복잡하고, 대부분의 치료제가 장기 복용 시 위장관계 궤양, 신장 기능 저하, 혈압상승 등의 부작용이 보고되어있다(Kim et al., 2021b). 이러한 이유로 부작용이 적은 천연물 소재가 치료제로써 각광받고있는 추세이다.

따라서 본 연구에서는 약용 식물의 항염증 잠재력을 평가하기 위한 지속적인 검사 프로그램의 일환으로써, 이삭물수세미 에탄올 추출물의 항산화 활성과 항염증 활성과 LPS 처리로 염증이 유도된 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 기본 분자 메커니즘에 대해 확인하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

실험재료

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), sulfanilamide, phosphoric acid, N-(1-naphthyl)ethylene diamine dihydrochloride 등은 Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA)에서 구입하여 사용하였다. Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8)는 Dojindo Lab. (Kumamoto, Japan)에서 구입하여 사용하였다. 단백질 분석에 사용된 항체(COX-2, iNOS, IL-1β, TNF-α)는 Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA)에서 구입하여 사용하였으며, 단백질 분리에 사용된 PRO-PREP lysis buffer는 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Cleveland, OH, USA)에서 구입하여 사용하였다. 대식세포 배양과 관련된 Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)와 fetal bovine serum (FBS)는 GIBCO (Gaithersburg, MD, USA)에서 구입하여 사용하였으며, Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)는 WeLGENE Inc. (Daegu, Republic of Korea)에서 구입하여 사용하였다. 다른 시약들은 Sigma grades로 구입하여 사용하였다.

추출물 제조

본 실험에 사용한 이삭물수세미(Myriophyllum spicatum L.) 시료는 경상북도 문경시 문경읍 요성리(2017년 6월)에서 인식형질이 있는 개체를 직접 채집하여 건조 파쇄하였으며, 본 표본은 국립낙동강생물자원관 수장고에 보관하고 있다(NNIBRVP60134). 식물의 동정은 ‘Korea Biodiversity Information System’에 의거하여 분류를 실시하였다(국가생물종지식정보시스템-Korea Biodiversity Information System, 2014). 이삭물수세미 에탄올 추출물을 조제하기 위해 건조 분말을 10배 중량의 70% 에탄올로 실온에서 24시간 동안 추출하였다. 에탄올 추출물을 여과지(Whatman No. 2, Advantec Co., Japan)로 여과한 후 용매를 Rotary evaporator (Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Tokyo, Japan)를 이용하여 제거하였고, 동결건조(Ilshin, Korea)를 거쳐 건조중량 대비 12.6%의 분말 시료를 얻었다. 이후 에탄올 추출시료는 dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)에 25 ㎎/mL의 농도로 녹여 –20℃에서 보관하였으며, 실험에 따라 적절하게 희석하여 사용하였다.

환원력과 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성 측정

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) 라디칼 소거 활성은 Cheel et al. (2005)의 방법을 응용하여 측정하였다. 농도별로 희석된 EMS 추출물(50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)을 각각 100 μL씩 취하여 DPPH radical (in MeOH, 0.2 mM) solution (100 μL)과 1:1 비율로 혼합하였다. 혼합물을 잘 섞어준 다음 암실에서 실온으로 30분 동안 방치하였다. 그 후 Cytation-3 microplate reader로 517 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다.

EMS의 환원력(reducing power)은 Yen and Chen (1995)의 방법을 응용하여 측정하였다. EMS 추출물(50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)을 phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.6)에 용해시키고 1% potassium ferricyanide (50 mL, 0.5 g)에 첨가하였다. 50℃에서 30분 동안 incubation한 후, 10% trichloroacetic acid (50 mL, 5 g)를 첨가하였다. 이후 100 μL 상층액을 증류수(100 μL) 및 0.1% ferric chloride (10 mL, 0.01 g)와 혼합하여 Cytation-3 microplate reader (Biotek, Shoreline, WA, USA)로 700 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Positive control은 Ascorbic acid (400 ㎍/mL)를 사용하였다.

세포배양

RAW264.7 대식세포는 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)가 함유된 DMEM 배지(Gaithersburg, MD, USA)를 이용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 조건에서 배양하였다. EMS 처리에 따른 세포생존율 정도를 측정하기 위하여 24-well plate에 RAW 264.7 대식세포를 well당 2×105개를 분주하고 12시간 배양하였다. EMS를 농도별(50, 100, 200, 400, 500 ㎍/mL)로 전처리하고, 1시간 뒤 LPS (500 ng/mL)를 처리하고 24시간 배양하였다. 이후 CCK-8 kit (Dojindo Lab., Kumamoto, Japan) manual에 따라 세포 생존율을 측정하였다(Kano et al., 2017).

Nitric oxide (NO)와 cytokine (PGE2, TNF-𝛼 및 IL-1𝛽) 측정

염증 활성을 확인하기 위해 염증 매개체인 NO와 cytokine 생성에 미치는 영향을 확인하였다. EMS 처리에 따른 NO와 cytokine 생성 억제 정도를 측정하기 위하여 24-well plate에 RAW 264.7 대식세포를 well당 2×105개를 분주하고 12시간 배양하였다. 이후 EMS을 농도별(50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)로 전처리 후 1시간 뒤 LPS (500 ng/mL)를 처리하고 24시간 배양하였다. NO 억제 측정은 배양액을 회수하여 Griess reagent [1% (w/v) sulfanilamide in 5% (v/v) phosphoric acid와 0.1% (w/v) naphthyl ethylene diamine dihydrochloride]와 1:1로 혼합하여 실온에서 10분간 반응시킨 후 ELISA reader (Biotek, Shoreline, WA, USA)로 540 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. PGE2, TNF-α 및 IL-1β의 염증성 cytokine 생성 억제 측정은 동일한 조건에서 배양된 배양액을 이용하여 ELISA kit manual에 따라 발현량을 측정하였다. 각각의 ELISA kits는 PGE2와 IL-1β는 R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) kit를 이용하였고, TNF-α는 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Cleveland, OH, USA) kit를 이용하였다(Jones et al., 2021; Nemmar et al., 2022; Sambon et al., 2020).

단백질 추출 및 Western blot analysis

단백질을 추출하기 위해 RAW 264.7 대식세포에 EMS (50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)을 전처리 후 1시간 뒤 LPS (500 ng/mL)을 처리하고 12시간 배양하였다. RAW 264.7 대식세포를 모은 다음, PBS로 세척하고 100 ㎕ PRO-PREP lysis buffer (0.5% Triton, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate (pH 7.2), 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 ㎍/mL leupeptin, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl urea, and 4 ㎍/mL aprotinin)를 사용하여 용해시켰다. 용해물을 1400 rpm, 4℃에서 20분간 원심 분리시켰다. 단백질 측정을 위해 상층액을 사용했다.

Nuclear상의 단백질을 추출하기 위해 RAW 264.7 대식세포에 EMS (400 ㎍/mL)을 전처리 후 1시간 뒤 LPS (500 ng/mL)을 처리하고 30, 60 min 배양하였다. RAW 264.7 대식세포를 모은 다음, PBS로 세척하고 100 ㎕ PRO-PREP lysis buffer를 사용하여 용해시켰다. NE-PER Nuclear Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)을 사용하여 핵과 세포질에서 단백질을 분리하여 사용하였다(Choi et al., 2010).

단백질 농도는 Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA)를 사용하여 측정하였다. 단백질을 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel에서 분리하고, Nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH, USA)으로 옮겼다. Membrane은 0.5% Tween 20과 5% nonfat dry milk가 함유된 Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4)으로 1시간 동안 blocking하였다. 이후 1차 항체와 함께 1시간 동안 배양 후, 2차 항체와 함께 실온에서 1시간 동안 배양하였다. 단백질은 ECL buffer를 이용하여 Chemidoc imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA)에서 검출하였다.

통계 처리

본 연구의 모든 실험 결과는 3회 실시한 독립적인 실험을 통해 얻은 값을 평균±표준편차로 나타내었으며, Graph Pad Prism 6 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)를 이용하여 one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test 실시한 후 Tukey test로 사후 검증하여 유의적 차이를 판단하였다.

결과 및 고찰

EMS의 항산화 활성

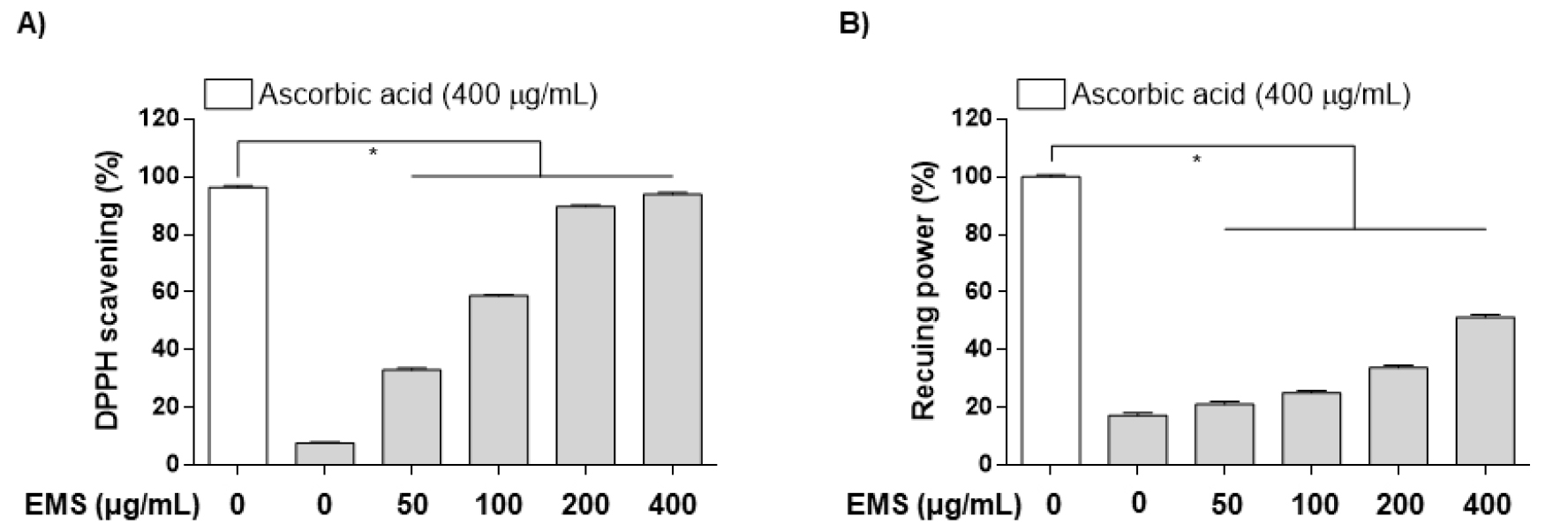

다양한 농도(0, 50, 100, 200 및 400 ㎍/mL)의 EMS를 사용하여 DPPH 라디칼 소거 분석을 수행하였다. Positive control로는 ascorbic acid (400 ㎍/mL)를 사용하여 평가하였다. EMS의 농도가 증가함에 따라 라디칼 소거능이 증가함을 관찰하였고, 200 ㎍/mL의 농도에서부터 ascorbic aicd와 유사한 라디칼 소거능을 보였다(Fig. 1A). 항산화제는 Fe3+/ferric cyanide 복합체가 ferrous 형태로 환원시키며, 700 ㎚에서 Perl의 Prussian blue 형성을 측정하여 그 농도를 확인할 수 있다. Fe3+를 Fe2+로 환원시키는 EMS의 능력을 이전과 동일하게 ascorbic acid를 positive control로 사용하여 평가하였다. 환원력은 EMS의 다양한 농도에 걸쳐 용량 의존적 증가함을 나타내었으며, 400 ㎍/mL의 EMS는 ascorbic aicd 대비 약 50%의 환원력을 나타내었다(Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Antioxidant (DPPH, Reducing power) activities of ethanol extract of Myriophyllum spicatum L. (EMS). (A) DPPH free radical-scavenging activity and (B) Reducing power of EMS obtained with bioprotease in an in vitro cell-free experiments. Each value is presented as the mean ± SD and is representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. The significance was determined by the Student's t-test (*p < 0.05, compared with control).

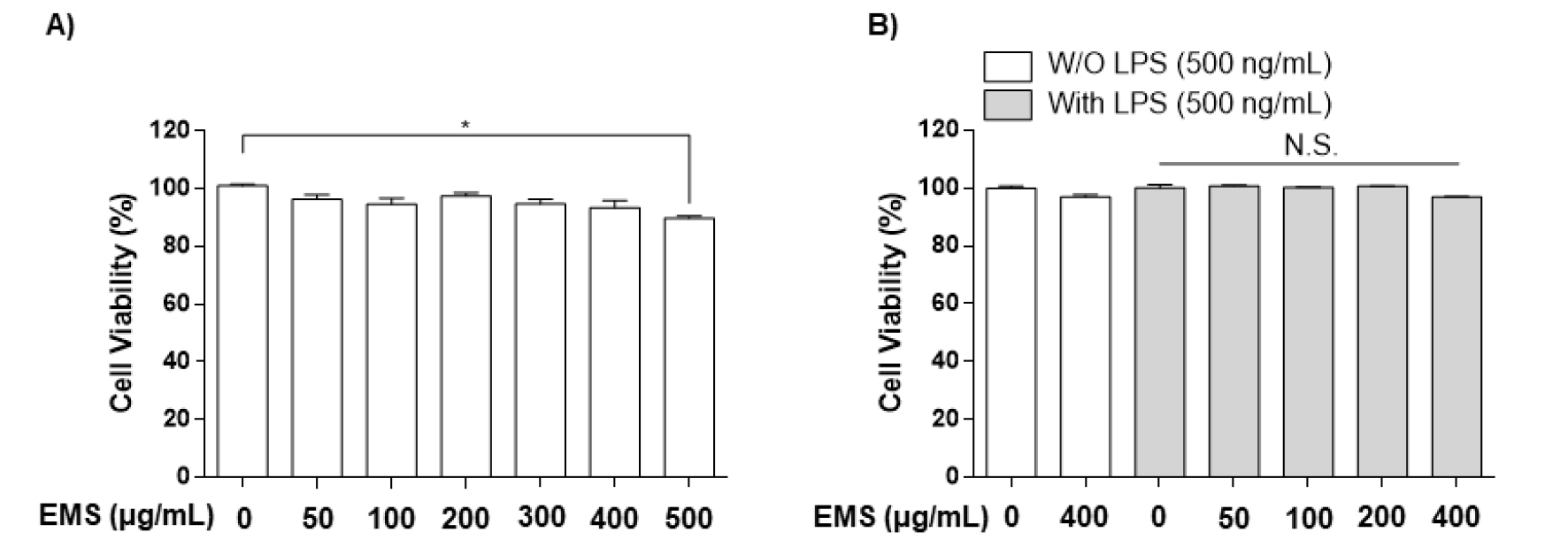

EMS가 RAW264.7 세포 생존에 미치는 영향

CCK-8 kit를 통해 EMS의 처리 농도가 RAW 264.7 대식세포에 독성을 나타내지 않는지 확인하였다. RAW 264.7 세포에서 농도별로 (50, 100, 200, 400, 500 ㎍/mL) 처리했을 때 독성은 나타나지 않았고, 최대 농도인 500 ㎍/mL에서 Cell viability가 90% 이하로 떨어지는 것을 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 2A). 따라서 본 연구에서 사용한 EMS의 최고 처리 농도는 400 ㎍/mL로 결정하여 사용하였다. 이후, EMS (50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)와 LPS (500 ng/mL)를 처리한 세포에서 생존율이 90% 이상으로 독성을 나타내지 않았다(Fig. 2B). 이러한 결과는 사용한 EMS 농도가 RAW 264.7 세포에서 무독성임을 나타내고, 이후 실험은 무독성 조건에서 항염증 활성 및 작용기전을 확인하였다.

Fig. 2.

Effect of EMS on the viability of RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EMS alone (A) or in combination with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 500 ng/mL) (B) for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, and the results are expressed as the percentage of surviving cells over control cells (no addition of EMS). Each value is presented as the mean ± SD and is representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. The significance was determined by the Student's t-test (*p < 0.05, compared with control group; N.S., not significant).

EMS가 iNOS, COX-2 발현 및 NO, PGE2의 생성에 미치는 영향

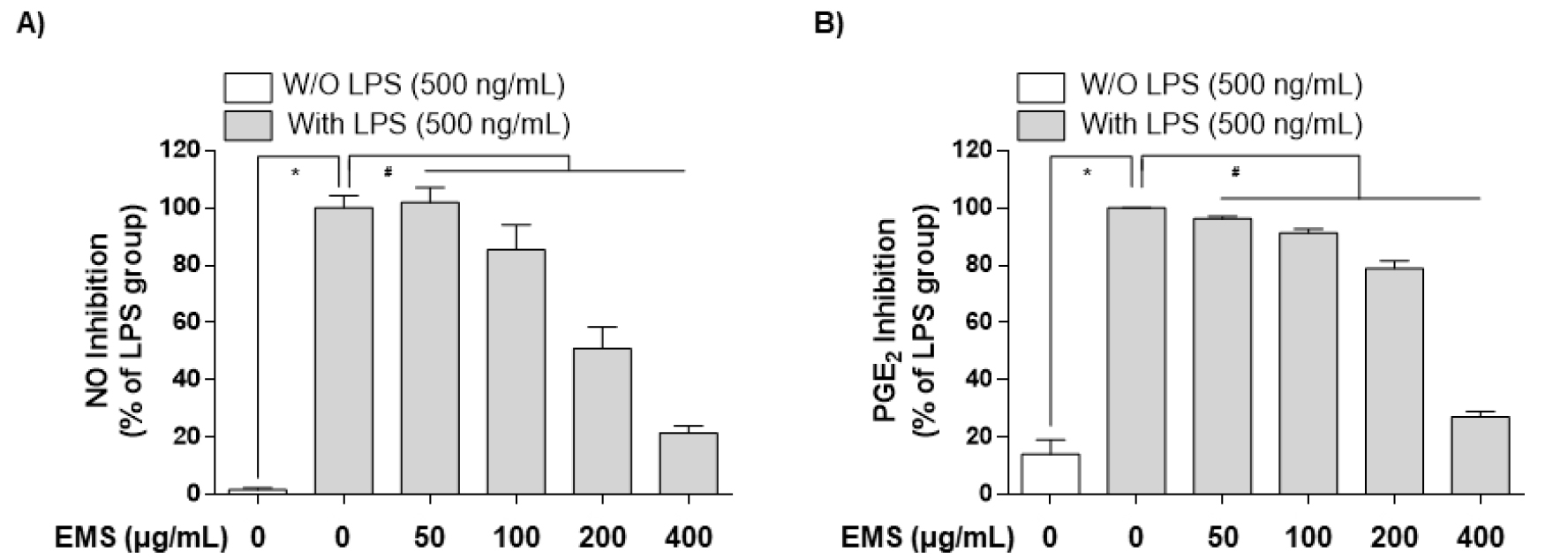

RAW 264.7 대식세포에 EMS를 농도별(50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)로 처리하여 NO와 PGE2의 생성 조절과 iNOS, COX-2의 발현에 영향을 미치는지 확인하였다.

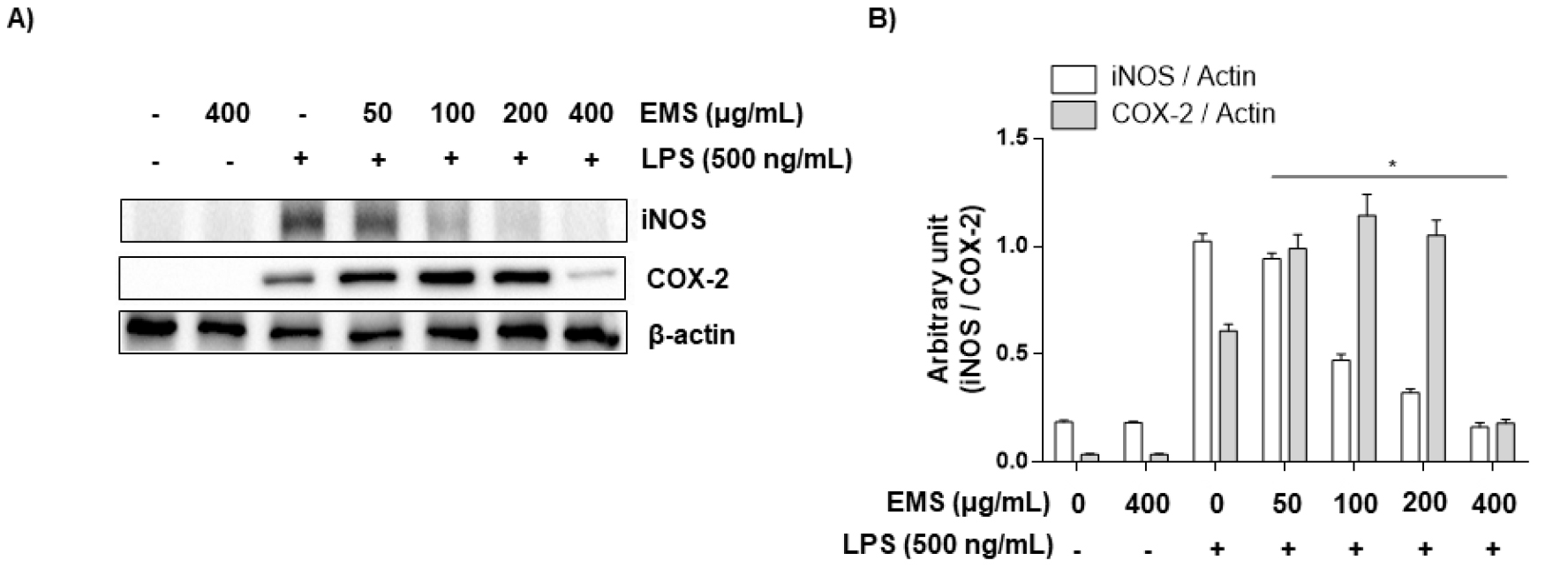

NO는 반응성이 큰 생체 생성분자로써, 면역조절에 중요한 역할을 하며 거의 모든 단계의 염증에 영향을 미치는데, L-arginine이 L-citrulline으로 nitric oxide synthase (NOS) 효소에 의해 합성될 때 생성된다(Guha and Mackman, 2001). 주요 합성효소인 inducible NOS (iNOS)는 평소에는 발현되지 않으나 LPS나 pro-inflammatory cytokine 등 외부자극을 받으면 발현되고 다량의 NO를 생성하게 되고 이는 염증을 유발하여 조직의 손상을 가져오는 것으로 알려져 있다(Coleman, 2001; Yoon et al., 2015). EMS 처리가 NO 생성에 미치는 영향을 측정하기 위하여 RAW 264.7 대식세포를 LPS로 자극시킨 후, NO의 생성 및 iNOS 단백질 발현 양상을 측정하였다. 그 결과 Fig. 3A에서 볼 수 있듯이 LPS (500 ng/mL)를 단독 처리하였을 때 NO 생성이 증가하였지만, EMS를 농도별로 (50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL) 전처리한 경우 농도 의존적으로 억제되었으며, iNOS 발현 또한 유의하게 억제됨을 보였다(Fig. 4).

적당한 양의 프로스타노이드(Prostanoid)는 항상성 유지에 필요하지만, 과량의 프로스타노이드 생성은 염증반응을 가속화시켜 다양한 염증성 질병을 야기시키고, 과도한 COX-2의 발현은 COXs 효소와 말단 PGE-synthases에 의해 아라키돈산(Arachidonic acid)으로부터 PGE2의 생성을 증가시킨다(Kawahara et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2021a; Needleman and Isakson, 1997). PGE2는 혈관 확장, 혈관 투과성 및 통증을 매개하고 염증성 질환의 발병에 중요한 역할을 한다(Westman et al., 2004). LPS로 유도된 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 PGE2 생성과 COX-2 단백질 발현양상을 확인하였다. 그 결과 NO 생성과 유사하게, LPS로 RAW 264.7 대식세포를 자극시켰을 때 염증 매개체인 PGE2의 생성이 증가되었다. 그러나 EMS 전처리한 경우는 NO와 달리 PGE2 증가가 최고 농도인 400 ㎍/mL의 농도에서 유의적으로 억제됨을 확인할 수 있었고(Fig. 3B), COX-2의 발현 양상 역시 유사하게 억제되는 것을 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Downregulation of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production by EMS in LPS‑stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of EMS (50, 100, 200, and 400 ㎍/mL) for 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (500 ng/mL) for 24 h, and nitrite content was measured using the Griess reaction. (B) The PGE2 concentration was measured in culture media using a commercial enzyme‑linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. Each value is presented as the mean ± SD and is representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. The significance was determined by the Student's t-test (*p < 0.05, compared with control group; #p < 0.05, compared with LPS).

Fig. 4.

Effect of EMS on LPS-stimulated iNOS and COX-2 expression in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with EMS (50, 100, 200, and 400 ㎍/mL) 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (500 ng/mL) for 24 h. (A and B) Cell lysates were prepared for western blot analysis, with antibodies specific for murine iNOS and COX-2, and for an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system. The experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. β-actin was used as the internal controls for the western blot analysis, respectively.

EMS가 pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-𝛼, IL-1𝛽)의 발현 및 생성에 미치는 영향

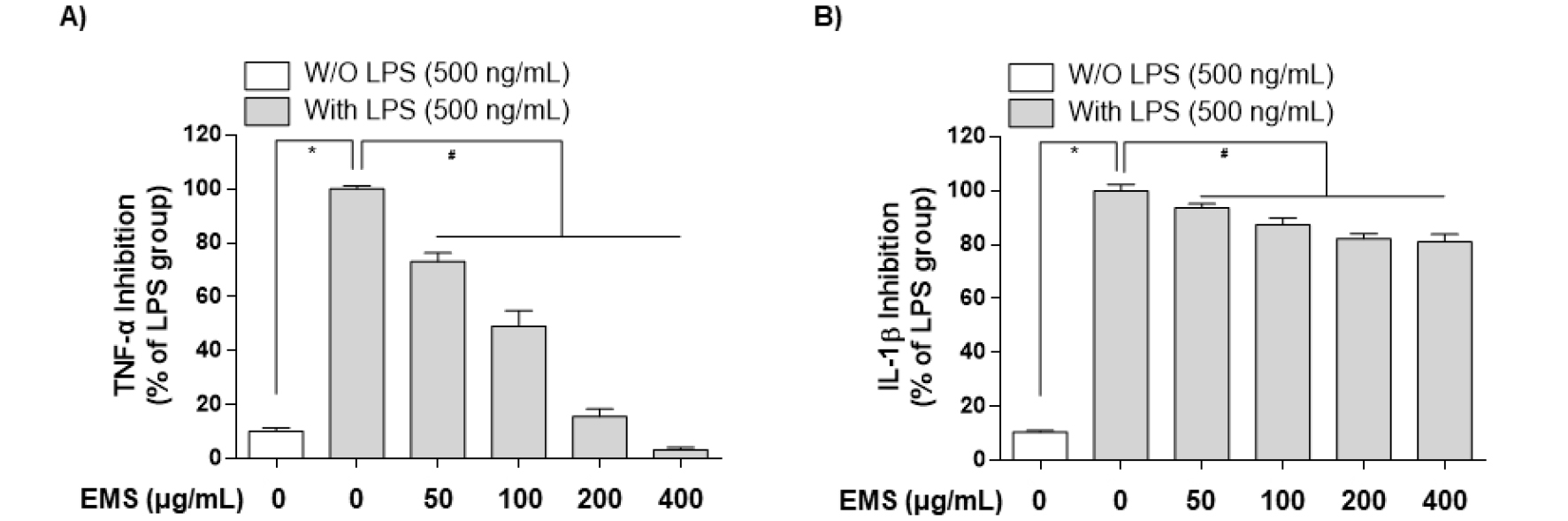

TNF-α는 염증, 면역, 세포 생존 및 종양 형성과 관련된 신호 전달 경로에 관여하는 다기능 사이토카인으로 알려져 있다(Laksmitawati et al., 2016). 이 사이토카인(TNF-α)은 염증 과정 중에 대식세포에 의해 생성되고(Laksmitawati et al., 2016; Seo et al., 2018), 여러 세포 간 및 혈관 세포 부착 분자를 조절함으로써 염증을 활성화시키며, 그 결과 염증 부위에 백혈구가 동원되도록 한다(Parameswaran and Patial, 2010).

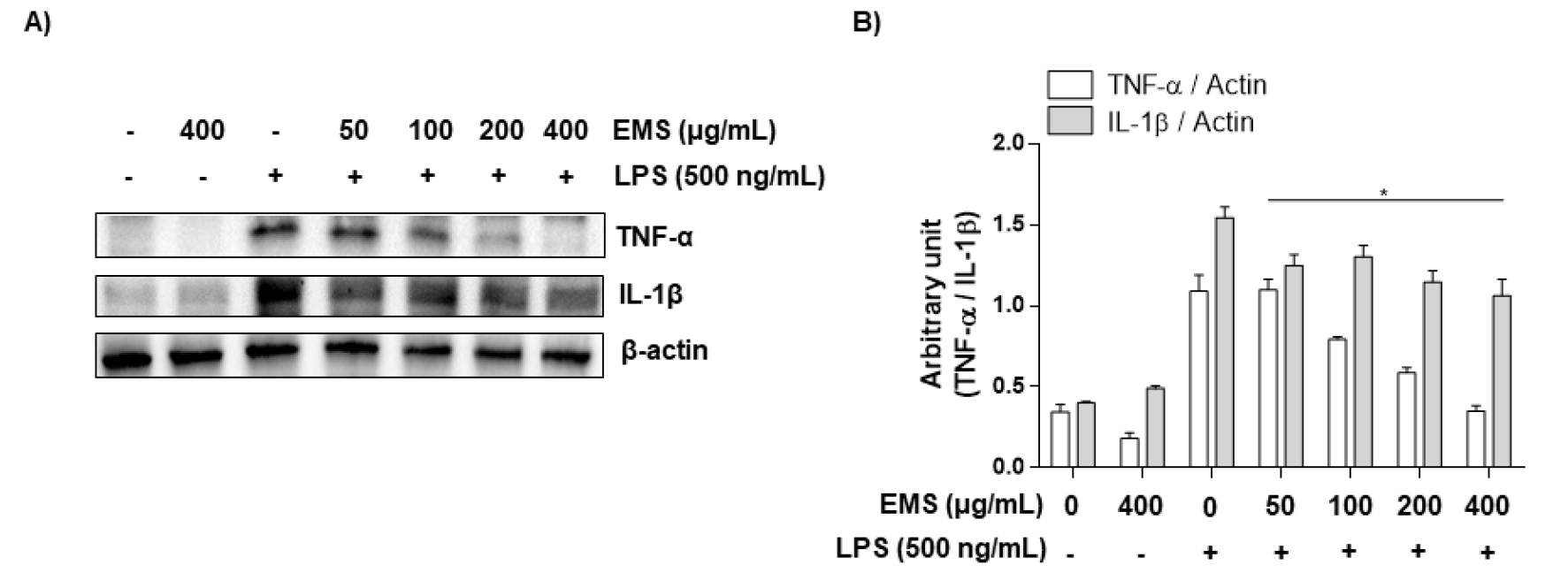

또 다른 pro-inflammatory cytokine인 IL-1β는 통증, 염증 및 자가면역 상태와 관련된 염증성 사이토카인으로(Lopez-Castejon and Brough, 2011; Ren and Torres, 2009), 수면 및 온도 조절과 같은 중요한 생체 항상성 기능을 가지고있다(Dinarello, 1996). 또한, IL-1β의 과잉 생산은 염증을 포함한 다양한 질병(신경병증성 통증, 혈관 질환, 다발성 경화증 및 알츠하이머병)에서 발생하는 병태생리학적 변화와 관련이 있다(Braddock and Quinn, 2004; Dinarello, 2004). 또한 병원체 등의 감염이나 자극에 의해 세포가 비정상적인 활성화가 이루어지면 염증 매개 인자(NO, PGE2)의 생성 증가와 함께 pro-inflammatory cytokine의 생성 또한 증가한다고 보고된 바 있다(Feghali and Wright, 1997). 더욱이, LPS로 자극된 대식세포에서 NO와 PGE2의 과도한 생산을 유도하는데 결정적인 작용을 하는 pro-inflammatory cytokine이 TNF-α와 IL-1β라고 알려져 있다(Babcock et al., 2004). 전 염증성 사이토카인을 억제할 수 있다면 염증뿐만 아니라 다양한 질병을 억제할 수 있을 것이다. 이러한 이유로 EMS가 pro-inflammatory cytokine의 조절을 통해 염증에 영향을 미치는지 확인하기 위하여 LPS로 유도된 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 TNF-α와 IL-1b의 생성과 단백질 발현양상을 확인하였다. Fig. 5에서 알 수 있듯, RAW 264.7 대식세포에 LPS를 단독 처리하였을 때 pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-1β)이 Control보다 상당히 증가됨을 확인하였다. 그러나 다양한 농도(50, 100, 200, 400 ㎍/mL)의 EMS를 전처리한 경우 LPS에 의해 증가된 TNF-α는 농도 의존적으로 억제되었고(Fig. 5A), IL-1β는 일정 수준 감소는 되었으나 유의미한 억제는 보이지 못했다(Fig. 5B). 또한, 단백질 발현양상에서도 ELISA 결과와 유사한 결과를 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Downregulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‑α and interleukin (IL)‑1β production by EMS in LPS‑stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of EMS (50, 100, 200, and 400 ㎍/mL) for 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (500 ng/mL). After incubation for 24 h, the levels of TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B) present in the supernatants were measured using ELISA kits. Each value is presented as the mean ± SD and is representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. The significance was determined by the Student's t-test (*p < 0.05, compared with control group; #p < 0.05, compared with LPS).

Fig. 6.

Effect of EMS on LPS-stimulated TNF‑α and IL‑1β expression in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with EMS (50, 100, 200, and 400 ㎍/mL) 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (500 ng/mL) for 24 h. (A and B) Cell lysates were prepared for western blot analysis, with antibodies specific for murine IL-1β and TNF-α, and for an ECL detection system. The experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. β-actin was used as the internal controls for the western blot analysis, respectively.

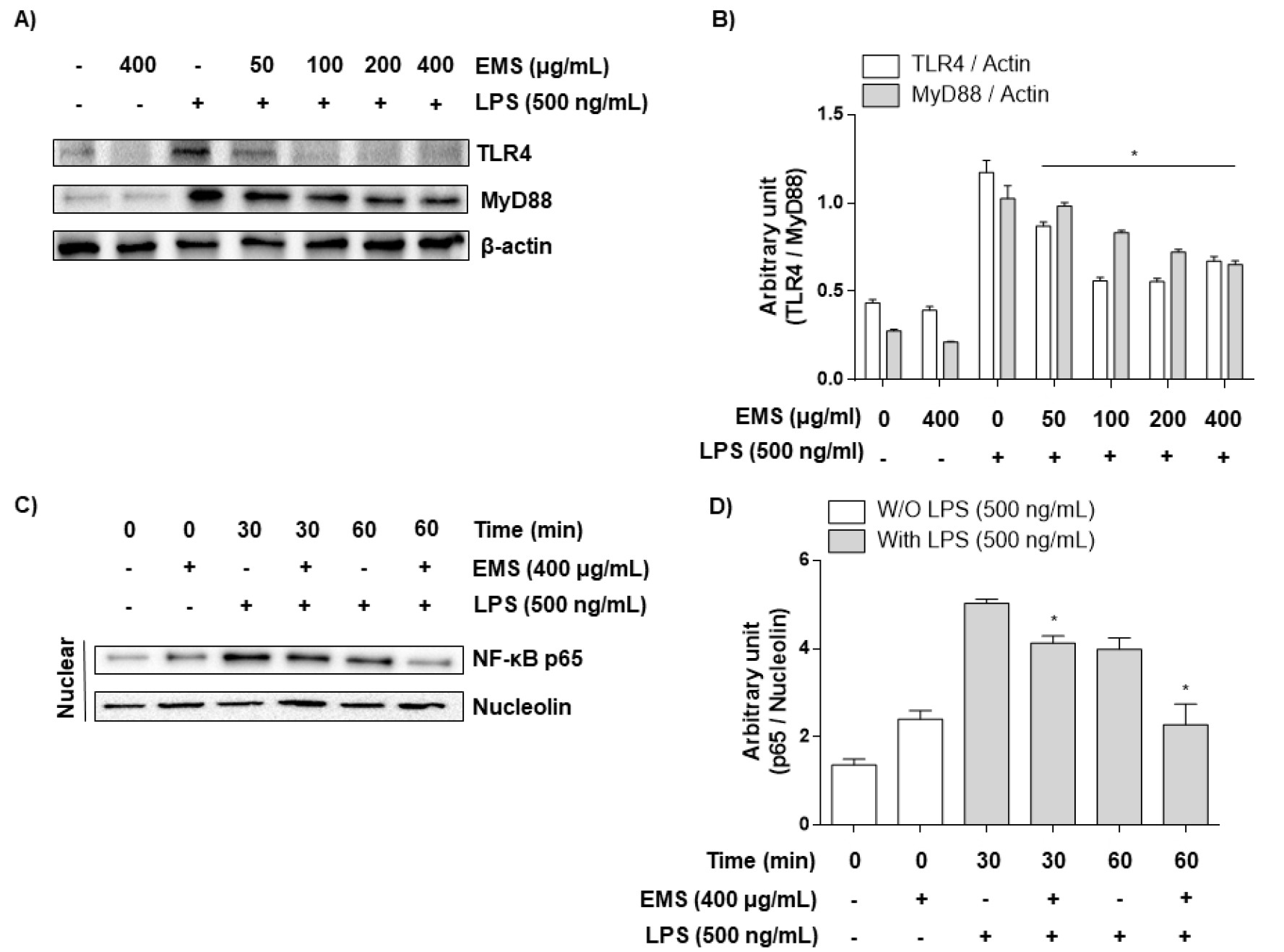

EMS가 TLR4/NF-𝜅B 신호전달 경로에 미치는 영향

Toll-like receptors (TLRs)는 LPS, 펩티도글리칸, 플라겔린, 이중 및 단일 가닥 바이러스 RNA 등과 같은 분자에서 발생하는 microbial motifs를 인식하는 PRR family다(Zhu et al., 2014). TLR family 중 TLR4는 염증반응을 시작하는 데 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Fang et al., 2013). LPS 등의 자극제에 의한 TLR4의 활성화는 어댑터 단백질인 MyD88을 통해 downstream인 NF-κB를 활성화시킨다(Li et al., 2011). 이를 통해 세포질 내에서 불활성의 형태로 존재하는 NF-κB의 p65 subunit이 인산화되어 활성화되고, 이것이 핵 내로 이동하여 염증매개 인자들의 합성을 위한 유전자를 전사하게 된다(Fujihara et al., 2003). EMS가 LPS로 유도된 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 early time (LPS 처리 후 30, 60 min)으로 NF-κB를 구성하는 p65 단백질의 인산화를 western blot으로 분석하였고, 그 결과 60 min보다 30 min 조건에서 강하게 translocation 됨을 확인하였다(Fig. 7C and D). 이를 통해 NF-κB의 upstream인 TLR4/MyD88의 조건을 LPS 처리 후 30 min으로 설정하여 TLR4/MyD88 단백질 발현양상을 확인하였다. 그 결과, Fig. 7에서 나타나듯이 RAW 264.7 대식세포에 LPS를 단독 처리하였을 때 TLR4와 MyD88이 Control보다 상당히 증가됨을 확인하였고, EMS를 전처리한 경우 LPS에 의해 증가된 TLR4/MyD88은 농도 의존적으로 억제됨을 보였다(Fig. 7A and B). 또한, early time에서 관찰한 nuclear상에서 LPS의 자극으로 유도된 p65의 인산화가 EMS에 의해 감소함을 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 7C and D). EMS에 의한 TLR4 및 MyD88의 감소는 downstream인 NF-κB의 활성화를 억제시켜 p65가 인산화를 통해 핵 내로 이동하는 것을 막아 염증매개 인자들의 합성을 위한 전사 활성이 이루어지지 않은 것으로 추정된다.

Fig. 7.

Effects of EMS on LPS-stimulated TLR4 and NF-κB expression in RAW 264.7 cells. (A and B) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were pretreated with EMS (50, 100, 200, and 400 ㎍/mL) 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (500 ng/mL) for 30 min. Cell lysates were prepared for western blot analysis, with antibodies specific for murine TLR4 and MyD88, and for an ECL detection system. (C and D) After 500 ng/mL LPS treatment with or without 400 μg/mL EMS for the indicated times(30, 60 min), the nuclear proteins were isolated, and the expression of NF-κB was determined by western blot analysis using an ECL detection system. The experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. Nucleolin and β-actin were used as internal controls for the western blot analysis, respectively.

적 요

이삭물수세미는 민간에서는 전초를 고름, 염증 등에 약용으로 사용하였으나, 염증에 대한 연구가 미비한 상황이다. 이에 본 연구에서는 이삭물수세미 추출물(EMS)의 항산화 효능과 항염증 효능을 분석하였다. 항산화 효능은 DPPH 라디칼 소거능과 환원력을 통해 산화적 스트레스를 통해 염증을 유발시킬 수 있는 ROS (Hong et al., 2020; Snezhkina et al., 2019)를 억제하는지 확인하였고, 항염증 효능은 염증 발현 인자인 LPS를 이용하여 RAW 264.7 대식세포에 염증을 유도한 뒤 pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-1β)과 염증 매개체(NO, PGE2)의 억제 및 TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB signaling pathway 발현 억제를 통해 확인하였다. 연구 결과, 항산화 효능에 있어서는 DPPH 라디칼 소거능과 Fe3+를 Fe2+로 환원시키는 환원력이 농도 의존적으로 증가함을 확인하였다. 무독성 상태에서 실험하기 위해 LPS와 EMS를 처리한 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 90% 이상의 생존율을 나타내는 조건에서 실험을 진행하였다. LPS로 염증이 유도된 RAW 264.7 세포에서 EMS는 염증 매개 인자의 발현 및 생성 억제(iNOS에 의한 NO 생성 및 COX-2에 의한 PGE2 생성 억제)와 pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α 및 IL-1β)의 생성 또한 억제하였다. 특이적으로 COX-2에 의한 PGE2 생성 억제에서는 고농도에서 작용함을 확인하였고, IL-1β에서는 약한 억제력을 보였다. 이후 signaling pathway에서 염증 전사인자 경로를 확인하기 위하여 TLR4/MyD88의 활성을 확인하였고, EMS 처리에 따라 농도 의존적으로 억제되는 것을 확인하였다. 이에 따라 염증 초기 단계에서 NF-κB p65가 nuclear로 들어가는 것을 억제하는지 확인하기 위해 early time (LPS 처리 후 30, 60 min) 조건으로 nuclear에서 p65 인산화를 확인하였다. 그 결과, LPS 자극으로 인해 증가된 p65 인산화가 EMS에 의해 부분적으로 억제됨을 확인하였다. 이상의 결과를 통해 LPS로 염증이 유도된 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 EMS가 COX-2에 의한 PGE2 생성 억제와 IL-1β의 생성에 있어 낮은 억제력을 가진 반면, iNOS에 의한 NO과 TNF-α 생성 및 TLR4/MyD88 singnaling pathway에 있어 강한 억제력을 가짐을 확인하였다. 결론적으로 EMS가 ROS를 제거하고 TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway를 억제함으로써 염증 인자들의 전사를 억제하고, 염증 인자 부분에서는 iNOS에 의한 NO 생성과 TNF-α 생성을 강하게 억제하여 RAW 264.7 대식세포에서 LPS로 자극된 염증을 억제하는 것으로 판단된다. 또한 TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB signaling pathway를 통한 pro-inflammatory cytokine과 염증 매개체와의 연관성에 대한 기초자료로 활용할 수 있는 근거 자료가 될 수 있을 것으로 생각된다.